The Aztec religion, with its complex system of beliefs and ceremonies ranging from the solemn to the bloody spectacular, has been studied through various primary sources that allow us to reconstruct its worldview.

These sources, though sometimes filtered through somewhat scandalised colonial eyes, offer an invaluable glimpse into a world where gods demanded sacrifices and ritual calendars set the pace of life.

Join me on this journey through the most fascinating documents and evidence of Aztec spirituality.

Aztec Religion Primary Sources

Pre-Columbian Codices: The Direct Voice of the Mexica

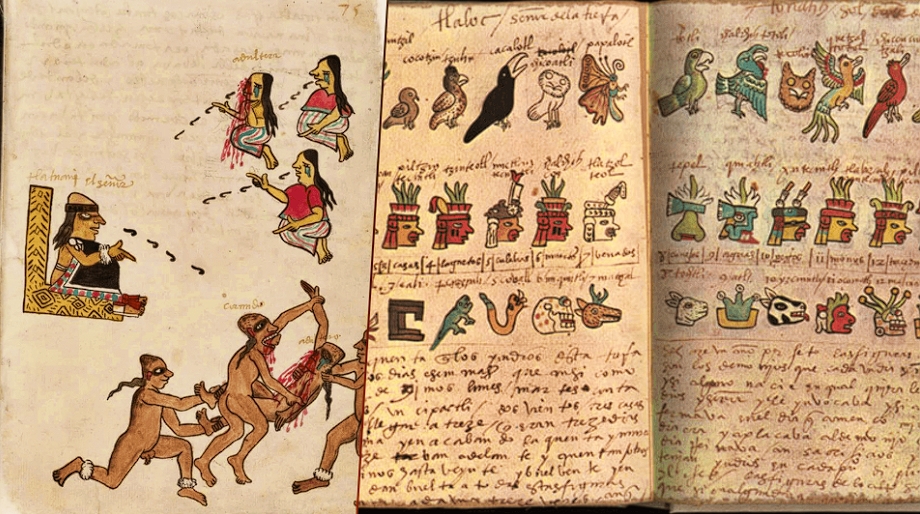

Among the most authentic sources are the codices created before the arrival of the Spaniards, when they could still write without fear of having their drawings branded as heresy.

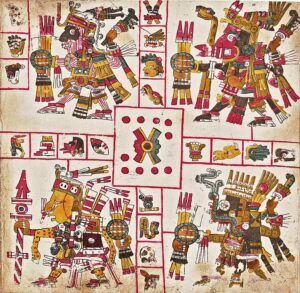

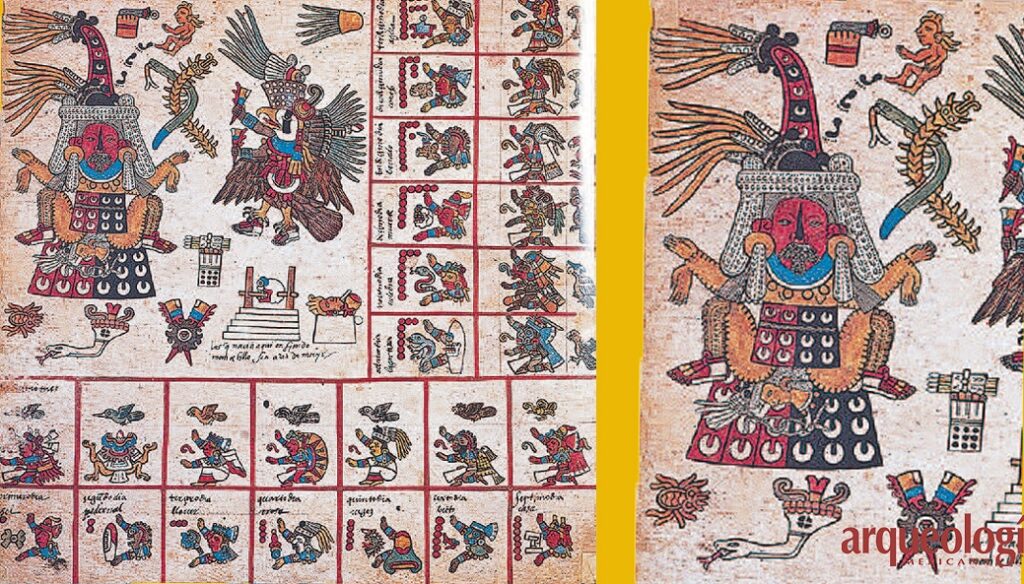

Codex Borgia

It is a pictorial manuscript full of religious iconography, ritual calendars and the most colourful deities, such as Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, each with a personality worthy of a mythological drama series.

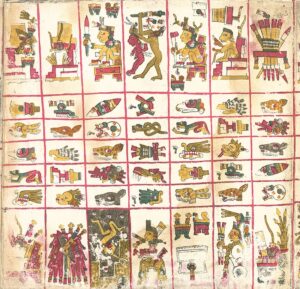

Borbonicus

It was probably written just before the Spanish arrived to turn everything upside down. This document provides a catalogue of religious festivities and rites that made any modern festival look like a children’s festival in comparison.

Codex Tudela (facsimile)

This work is a ‘cultural encyclopaedia’ containing information on Aztec idolatry, religious festivals and rituals as well as the Aztec calendar. Although the original has been lost, the facsimile collects knowledge gathered by old and young Aztec informants within a few years after the end of the empire.

Colonial Sources: Stories Between Documentation and Frailuno Gossip

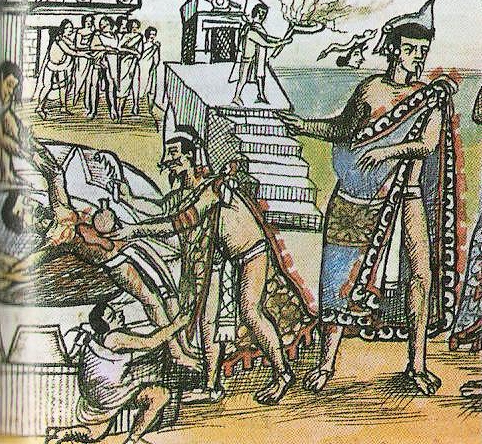

After the conquest, friars and historians set about writing everything they could about the Aztecs, often with pen in one hand and cross and sword in the other.

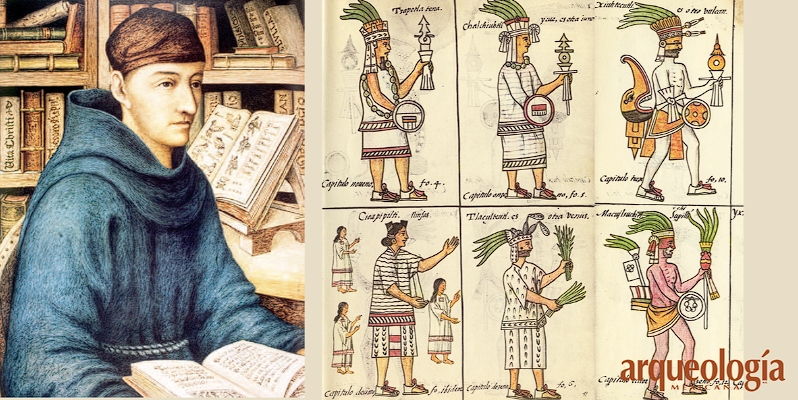

The Florentine Codex

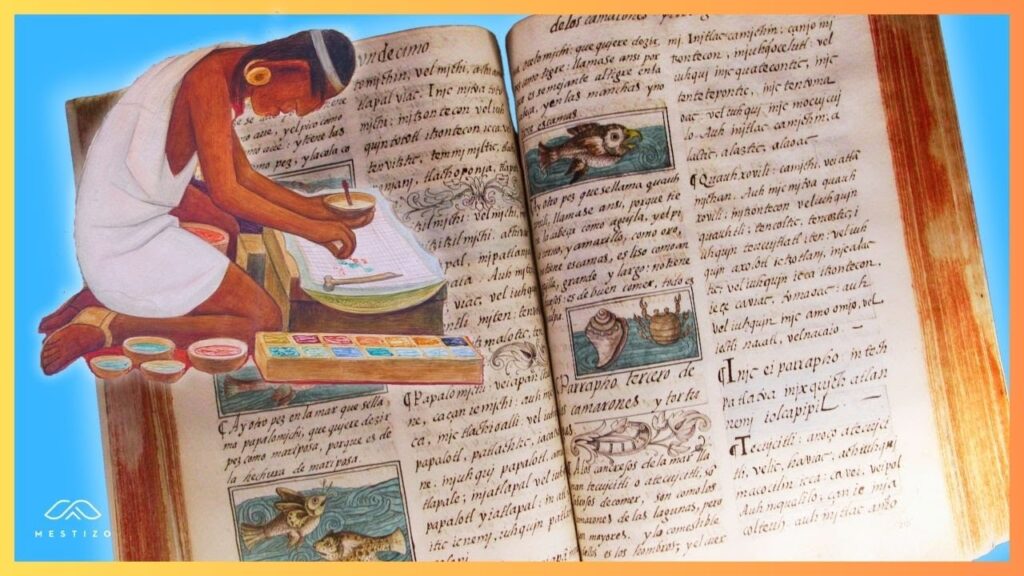

Directed by Bernardino de Sahagún, it is an ethnographic encyclopaedia written in Nahuatl with the help of native informants, who probably told things with the patience of one who explains technology to his grandparents.

Its 12 volumes detail rituals, myths and descriptions of gods with illustrations by tlacuilos, the indigenous artists of the time.

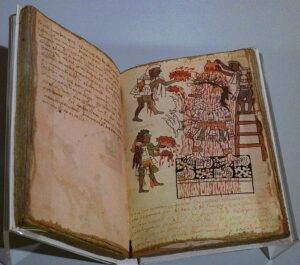

History of the Indies of New Spain

Friar Diego Durán, for his part, left us the ‘History of the Indies of New Spain’, in which he recounted religious festivals and sacrifices with a mixture of fascination and horror. Of course, always with the intention of making the Aztecs look as if they were in need of Christian enlightenment, but we cannot deny that his testimony gives us a fairly detailed backstage view of the Mexica religion.

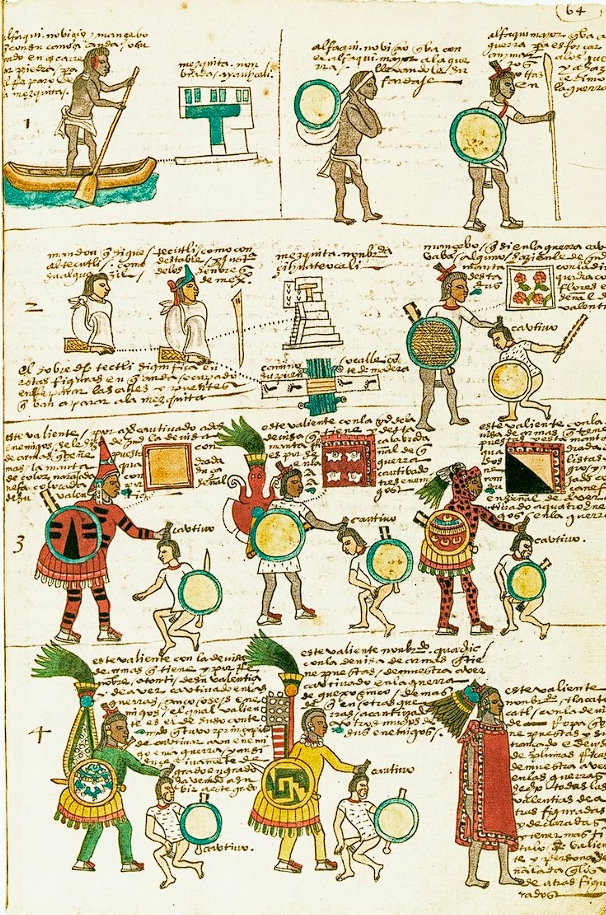

The Codex Mendoza

Commissioned by Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, it is like a travel guide to the period: history, tributes, daily life and, of course, a glimpse of the rituals and ceremonies they organised. There are no selfies, but the religious pictograms are quite illustrative.

Aztec Religion Primary Sources and the Clash Between Evangelism and Indigenous Truths

It is important to remember that many of these sources, while valuable, have European biases. Sahagún and Durán wrote with the intention of documenting, but also of evangelising, which may have influenced how they portray certain rituals.

It is therefore essential to contrast these texts with pre-Columbian codices and archaeological evidence to ensure that we are not viewing the Aztecs through the filter of a medieval horror film.

Aztec Religion secondary Sources

Religious Archaeological Evidence

Excavations at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán have brought to light offerings with animal remains, sculptures of gods and funerary urns that confirm many of the practices described in the codices. Surprise! Not everything was the invention of the Spanish chroniclers.

Among the most striking finds is the sculpture of Coyolxauhqui, the unfortunate sister of Huitzilopochtli, who learned the hard way that it was not a good idea to mess with the god of war.