The Aztec calendar was a complex comprising two separate systems that together created a 52-year cycle. Each system served an important purpose for the Aztecs in their daily and religious lives. Not only did they serve as a means to determine the passage of time, but both calendars provided guidance for the timing of religious ceremonies, festivals, and agriculture.

Aztec Calendar Structure

Two independent calendar systems comprised the 52-year cycle that is often known as the Calendar Round. At the end of each Calendar Round, the 52-year cycle began anew.

The first of these calendar systems, the tōnalpōhualli, consisted of a 260-day cycle. This calendar served as an orientation for religious and spiritual objectives.

The second calendar was called xiuhpōhualli and functioned as a year count with 365 days divided into months.

Xiuhpōhualli – The Year Count

The xiuhpōhualli, or the year count, was structured around solar cycles and was considered an agricultural calendar. However, time keeping was not its only purpose. The year count calendar dictated when festivals and ceremonies should be held. The 365 days were broken into two groups – 360 named days and 5 unnamed days. Each of the 360 named days were further divided into 18 periods of 20 days each.

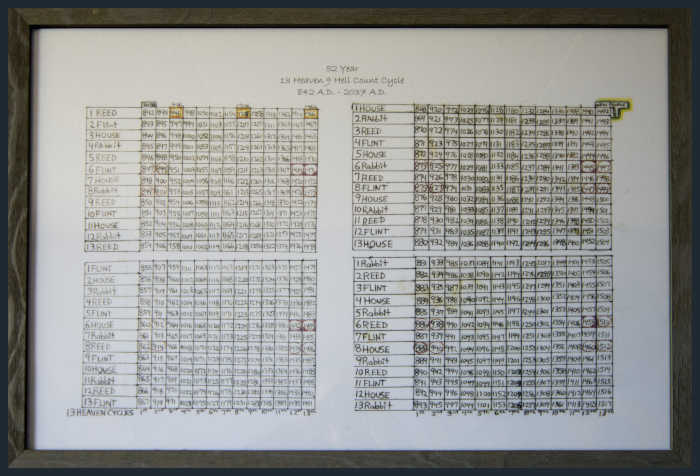

Years were named based on the names Rabbit, Reed, Flint Knife, and House. They were then given sequential numbers up to 13, ensuring that once each name and number had been used, a full calendar round of 52 years had been completed.

The last 5 unnamed days of each year were considered inauspicious or unlucky. These days were added in an attempt for solar accuracy.

Tōnalpōhualli – The Day Count

Tōnalpōhualli, sometimes called the day count calendar, was considered one of the most important parts of the Aztec calendar system. This calendar was used to determine what god the day belonged to. Aztecs considered this significant in order to retain balance between the multiple gods.

Each of the 260 days in this calendar were broken into 20-day periods in which each day had its own name, deity, and symbol. Every 13 days, an Aztec week would pass. At this point, the number of the day would revert to 1 while the name, deity, and symbol would continue to 20.

The day count calendar was not based on either solar or lunar patterns. Instead, it has been hypothesized that these numbers were chosen as they closely align to the human gestation period. Regardless of how these numbers were constructed, the day count calendar and year count calendar aligned roughly every 52 years.

Deities

In the day-counting calendar, called tonalpohualli, each day was assigned a diurnal symbol that was associated with a deity. In addition, the number preceding the day sign was also related to a spirit or force that could determine the nature of a day. These two pieces of information helped determine what rituals should be performed that day.

In order, the 20-day signs and god associated with them were:

- Crocodile – Tonacatecuhtli, god of fertility and new beginnings

- Wind – Quetzalcoatl, god of intelligence

- House – Tepeyollotl, god of night and echoes

- Lizard – Huehuecóyotl, the deity of deceit and stories.

- Serpent – Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess of water and the origin of life.

- Death – Tecciztecatl, god of the moon

- Deer – Tlaloc, deity of rain and thunderstorms.

- Rabbit – Mayahuel, goddess of fertility

- Water – Xiuhtecuhtli, god of fire

- Dog – Mictlantecuhtli, god of death

- Monkey – Xochipili, god of flowers and creativity

- Grass – Patecatl, god of healing

- Reed – Tezcatlipoca, god of time and memory

- Jaguar – Tlazolteotl, goddess of the earth

- Eagle–Xipe Totec, god of rebirth and spring time

- Vulture – Itzpapalotl, goddess of sacrifice and purification.

- Movement – Xolotl, god of sickness

- Stone Knife – Chalchihuihtotolin, god of sorcery

- Rain – Tonatiuh, god of the sun

- Flower – Xochiquetzal, goddess of flowers and love

Aztec Festivals and Ceremonies

Within both the day and year calendar, there were many Aztec celebrations. Several of these involved human sacrifice, although others required only animal or a blood sacrifice. Each month, in the annual calendar, a festival was held.. These occurred on the first day of that particular period.

Ceremonies and festivals occurred for many reasons, but often were associated with planting, harvest, hunting, and fertility. Of particular focus for many festivals was agriculture. Priests organized all ritual and ceremony, while the remainder of the Aztecs participated in feasts and festivities.

In Spring, festivities occurred to honour Xipe Totec to invoke fertility and rebirth. The rituals associated with this included human sacrifice and lasted for 20 days. During the 20-day festival, captured warriors were sacrificed and flayed. Military ceremonies also typically took place during this festival.

An important festival took place at the end of each 52 year calendar round when the 2 calendars aligned. During this festival called New Fire Rites, all fires were doused, and the city was drenched in darkness. A man was then sacrificed, and a fire was stared in his chest. From this fire, all fires in both homes and temples were relit.

At the end of the 360 named days, no festivities would occur for the 5 unnamed days at the end of the year. This unlucky period of time consisted of fasting and waiting for the year cycle to begin anew.

Aztec Calendar Stone

The Aztec Calendar Stone, sometimes called the Sun Stone, is an iconic Aztec stone sculpture. In the centre of the stone is the face of the sun deity, Tonatiuh. On either side of the face, 2 claw like hands clutch human hearts. Intricate carvings and symbols surround the face in increasingly larger circles.

From the centre, the first circle represents the four previous eras before the creation of the Sun Stone. The second circle represents the 260-day count. The third circle contains five points, likely relating to cardinal points. In the fourth and final ring, there are 2 serpents and a carving thought to be the date the stone was created.

The specific purpose of the Calendar Stone is unknown, however, it is thought to be of religious or ceremonial uses.

You may be interested to read: Aztec Food: Flavours of Ancient Tradition